How Animal Classification Cards Turned Confusion into Curiosity

How Animal Classification Cards Turned Confusion into Curiosity

by Dewi Griffith Ph.D

Only Ms. Rina’s science mornings could create such a chaotic scene.

Ms. Rina had placed a large number of animal flashcards on a table in front of her.

“Elephants lay eggs, Teacher!” was shouted from one side of the class.

“No way! It’s birds that do that!” retorted another.

“But snakes are slimy. That means they are fish!”

Ms. Rina smiled. She had planned a wonderful lesson on types of animals, but in front of her was a wild bunch of children flinging about everything she had tried to teach them.

Kids could recognise animals by sight. They did not know about the specific, scientific traits that made each animal unique. For them, there was only a lion, a frog or a parrot.

Ms. Rina realised that before young children could memorise they had to see, touch, and sort.

The topics that we cover include the following:

Beyond Theory: The Challenge of Making Knowledge Real

The Game Changer: Introducing Animal Classification Cards

More Than Just Sorting: The Hidden Learning Engine

Build Your Animal Card Game: A Quick-Start Guide

The Shared 'Aha!' Moment

References

Beyond Theory: The Challenge of Making Knowledge Real

Little ones love the concrete.

But many scientific concepts, like animal classification, are not concrete or visible.

Developmental psychologist Jean Piaget (1964) observed that preschoolers (2–7 years, or Piaget’s “preoperational stage”) “think intuitively rather than logically.”

They perceive objects and events, but have a hard time with abstractions and long explanations.

Ms. Rina’s question, “What makes a reptile?” was met with a sea of confused faces.

The children needed concrete examples they could see to help them understand the concept.

The Game Changer: Introducing Animal Classification Cards

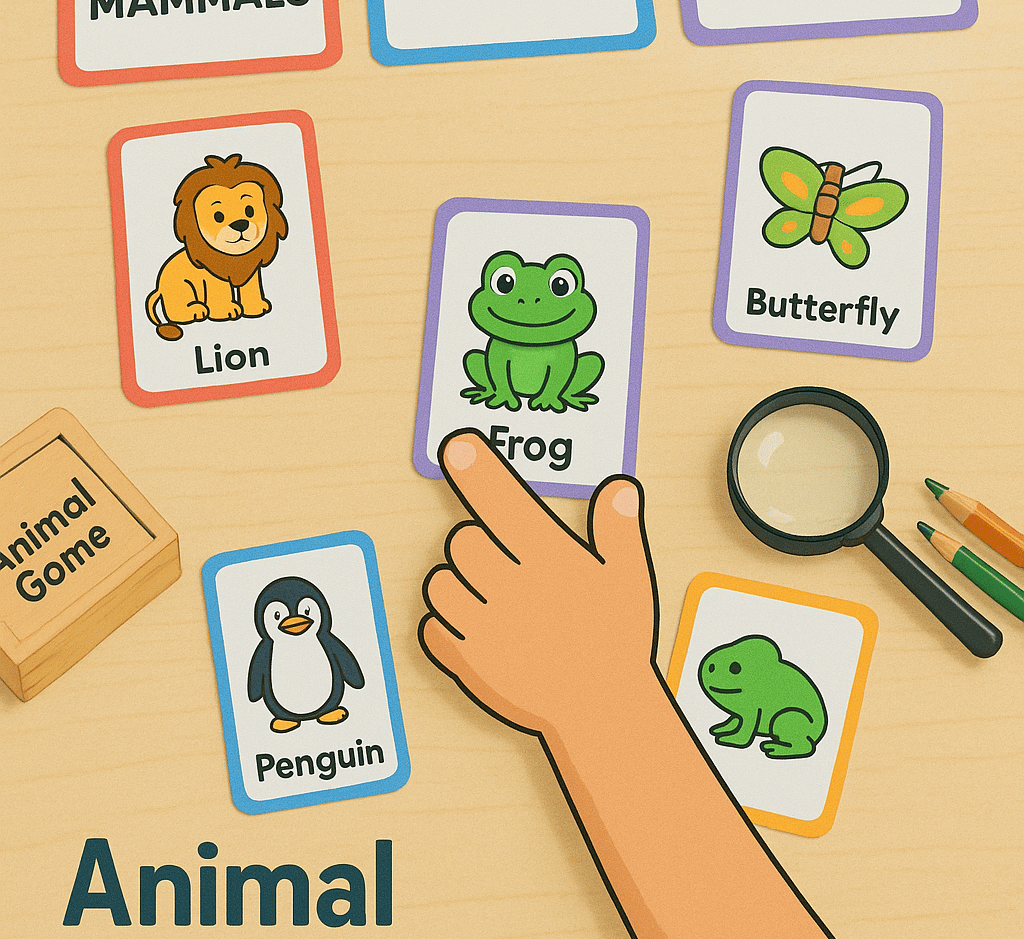

The following day Ms. Rina returned with a new tool: Animal Classification Cards.

Each card featured:

A large, realistic animal photo

The animal’s name, printed in big letters

A pastel border that indicated its group (blue for mammals, yellow for birds, green for reptiles, orange for amphibians)

She laid them out on the floor and announced:

“Today, you’re not students—you’re animal detectives. Can you figure out which animals belong together?”

The children leaned forward eagerly.

They grabbed cards, flipped them over, studied the clues, and began sorting.

Some kids sorted by movement.

Some by diet.

But with a few nudges — “Do they have fur or feathers?” “Do they have eggs or babies?” — their sorting went from instinctive to logical.

By the end of the lesson, four colored piles had formed on the carpet:

🐾 Mammals – elephant, cat, whale, kangaroo

🦜 Birds – penguin, eagle, parrot, ostrich

🐍 Reptiles – snake, turtle, lizard, crocodile

🐸 Amphibians – frog, salamander, toad

The children cheered as they understood they had successfully completed the task together.

Build Your Animal Card Game: A Quick-Start Guide

You can create this activity easily at home or in class. Here’s how:

Animal Classification Card Template

Categories:

🐾 Mammals

🦜 Birds

🐍 Reptiles

🐸 Amphibians

Materials:

Cardstock or laminated paper for durability

20–24 animal pictures (4–6 from each group)

Colored borders or stickers (1 colour per category)

Optional: storage envelope or box, labeled “Animal Sort Game”

Instructions:

Print and cut the animal cards.

Mix all cards into a pile.

Ask children to sort the cards into four groups based on the features:

Mammals have hair or fur, give birth to live young, and breathe air.

Birds have feathers and lay eggs.

Reptiles have scales and usually lay eggs on land.

Amphibians live both in water and on land, with moist skin.

Review together using the colored borders as visual cues.

Ask children to explain their reasoning: “I put the penguin with birds because it has feathers.”

References

Montessori, M. (1949). The Absorbent Mind. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Piaget, J. (1964). Development and Learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 2(3), 176–186.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press.

Other articles you might like

Learning Through Play

Home Reading Tips

DIY Learning Materials